Synchronicity?…

…Synchronicity!

Synchronicity, from Wikipedia: (Okay, yeah, I know it’s Wikipedia, but still..!)…

“Synchronicity (German: Synchronizität) is a concept first introduced by analytical psychologist Carl G. Jung ‘to describe circumstances that appear meaningfully related yet lack a causal connection.’ Jung held that to ascribe meaning to certain acausal coincidences can be a healthy, even necessary, function of the human mind – principally, by way of bringing important material of the unconscious mind to attention. This further developed into the view that there is a philosophical objectivity or suprasubjectivity to the meaningfulness of such coincidences, as related to the collective unconscious.”

____________________

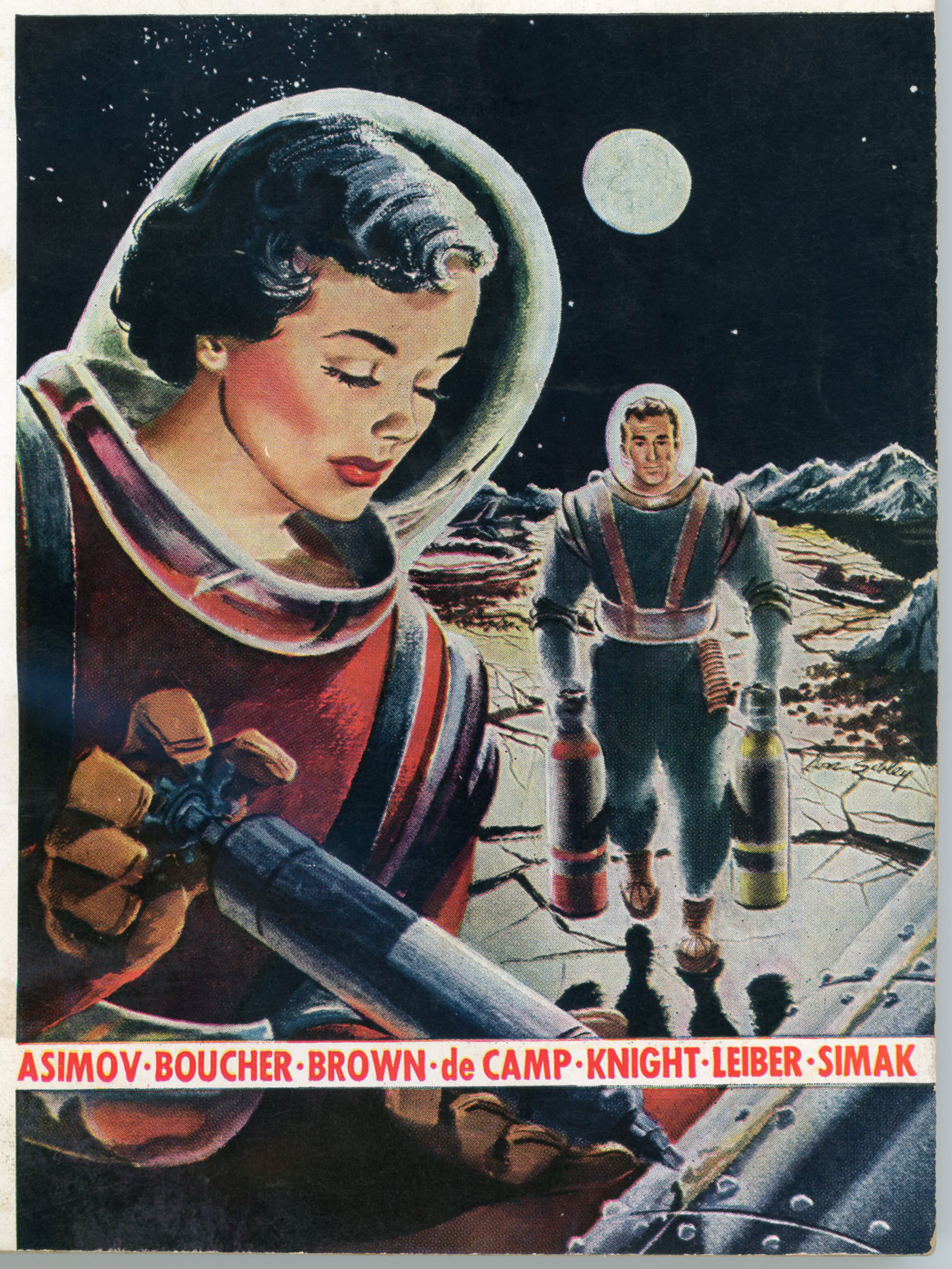

So I was perusing; leafing through; skimming; wandering within, the pages of my copies of Galaxy Science Fiction, and chanced upon the issue of November, 1950, which features Don Sibley’s cover art for Fredric Brown’s short tale “Honeymoon in Hell”. The issue also contains part two of Clifford Simak’s three-part serial “Time Quarry” (retitled in novel form as Time and Again) and notably, Damon Knight’s “To Serve Man”, which was the basis for Twilight Zone Episode # 89, adapted for television by Serling himself and broadcast under the same title on March 2, 1962.

Remarkably for its cultural significance, Knight’s story is only six pages long. It also features David Stone’s illustration of a Kanamit, the tale’s extraterrestrial protagonist (or, one of the protagonists, for those Kanamits seem to be pretty indistinguishable from one another) which portrayal is utterly unlike the aliens as depicted in the Twilight Zone adaptation.

____________________

Close-up of Don Sibley’s cover art.

Red uniform? Soviet Cosmonaut, Anna Borisovna.

Blue uniform? American Astronaut, Captain Raymond F. Carmody.

____________________

Interesting. But, for all its prominence in pop culture, “To Serve Man” has never been one of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes, for the plot, though ending with a twist that’s as disturbing as it is clever – o k a y, I’ll grant it t h a t – is really quite simple in concept. Unlike many ‘Zone episodes, “To Serve Man”, though obviously and easily adaptable to television because of the simplicity and brevity of the original story, is one of the series’ more middling episodes because it simply does not have anywhere near the psychological and even moral depth of the numerous other, more complex episodes. The best of these involve individuals confronting and often (but not always!) overcoming their moral, psychological, and even spiritual “ghosts” in settings where themes of science fiction, the paranormal, and occasionally the supernatural – alone, or in combination – while inherent to plot and setting, are actually incidental to themes of personal transformation. And if not transformation, at least an epiphany.

So, suppose that every aficionado of the series has their own (!) favorite episodes, here are mine:

The Invaders (Brilliant solo performance by Agnes Moorehead.)

Nightmare At 20,000 Feet (But of course!)

__________

My favorite episode of all?

Nervous Man in a Four-Dollar Room

A superb production.

A story of great complexity, based upon an extraordinarily simple premise, with an excellent near-solo performance by Joe Mantell.

Outstanding, by all measures.

__________

But, getting to the subject at hand. Or more accurately, the image at hand.

Within the November, 1950 issue of Galaxy is another short story; one by Fritz Leiber, Jr., entitled “Coming Attraction”, (You can listen to Atomic Julie’s audio version here.) As summarized (in greater depth) at Wikipedia, the tale is set within a mostly uninhabitable Manhattan – rendered so by a Soviet “Hell Bomb” – amidst an ongoing war between the United States and (former) Soviet Union. The protagonist, British citizen Wysten Turner, has ventured to New York City to obtain grain in exchange for electronic equipment which may be intended for an American military installation on the moon.

The story, however, features none of the standard science fiction tropes, such things as transformative technology, extraterrestrials, space voyages, time travel, and genetic engineering being quite absent. Instead, the plot focuses on social interactions between men and woman, through the experience of Turner himself, in a society that has the air of a social dystopia – albeit a bland, soft, depressing sort of sociological dystopia rather than one characterized by material want or technological regression – where women have taken to wearing masks as a taken-for-granted accoutrement of everyday attire.

Unsurprisingly, given Leiber’s extraordinary literary skill, the story is well constructed; it’s “tight”, moving forward at a steady pace with no extraneous detail, tedious digressions, or slack. Yet with that, I still don’t think it’s one of Leiber’s best efforts, and I find it very odd that it was deemed worthy of inclusion in volume one of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, published two decades later. While certainly interesting in concept and well executed on a technical level, it’s just not one of Leiber’s strongest tales, or really, that strong of a tale at all. Though it was included in Ballantine Books’ The Best of Fritz Leiber, it’s easily outshown by most of the other tales in that anthology, particularly “Gonna Roll The Bones” (1967), and “A Deskful of Girls” (1958), the latter showing Leiber’s originality at its best.

So much for words.

And pictures?

The story is illustrated by single thematic image, created by Paul Callé, which – soon after you begin reading the tale – leaves no room for ambiguity.

Well, if these were “average” times (but there are no more average times, and I doubt if any era has ever been “average”, anyway) the reader would take a look, think “hmmm, interesting,” and much for any story, flip the page and move on.

Alas, times are no long average, and they may not be so again in our lifetimes. I wish that were not so, but so it is; so may be. (But, for how long?)

Did Paul Callé’s art, of a mask as a fashion statement (in the story, it serves no other function), in some unanticipated way portend the year 2021? And beyond?

She just sat there.

I couldn’t even tell if she was trembling.

I tried to read a message in her eyes through the mask.

“I’ll take you away,” I said to her.

“I can do it. I really will.”

He smiled at me.

“She’d like to go with you,” he said.

“Wouldn’t you, baby?”

“Will you or won’t you?” I said to her.

She still just sat there.

He slowly knotted his fingers in her hair.

“Listen, you little vermin,” I snapped at him.

“Take your hands off her.”

He came up from the seat like a snake.

I’m no fighter.

I just know that the more scared I am, the harder and straighter I hit.

This time I was lucky.

But as he crumpled back, I felt a slap and four stabs of pain in my cheek.

I clapped my hand to it.

I could feel the four gashed made by the dagger finger caps,

and the warm blood oozing out from them.

She didn’t look at me.

She was bending over little Zirk and cuddling her mask to his cheek and crooning:

“There, there, don’t feel bad, you’ll be able to hurt me afterward.”

There were sounds around us, but they didn’t come close.

I leaned forward and ripped the mask from her face.

I really didn’t know why I should have expected her face to be anything else.

It was very pale, of course, and there weren’t any cosmetics.

I suppose there’s no point in wearing any under a mask.

The eyebrows were untidy and the lips were chapped.

But as for the general expression, as for the feelings crawling and wriggling across it…

Have you ever lifted a rock from damp soil?

Have you ever watched the slimy white grubs?

I looked down at her, she up at me.

“Yes, you’re so frightened, aren’t you?” I said sarcastically.

“You dread this little nightly drama, don’t you?

You’re scared to death.”

And I walked right out into the purple night,

still holding my hand to my bleeding cheek.

No one stopped me, not even the girl wrestlers.

I wished I could tear a tab from under my shirt,

and test it then and there, and find I’d taken too much radiation,

and so be able to ask to cross the Hudson and go down New Jersey,

past the lingering radiance of the Narrows Bomb,

and so on to Sandy Hook

to wait for the rusty ship that would take me back over to seas to England.

References

Paul Callé, at Wikipedia

Paul Callé, Beyond All Weapons

Paul Callé, By The Stars Forgot

Coming Attraction, at Wikipedia

Fritz Leiber, Jr., at Tellers of Weird Tales