________________________________________

________________________________________

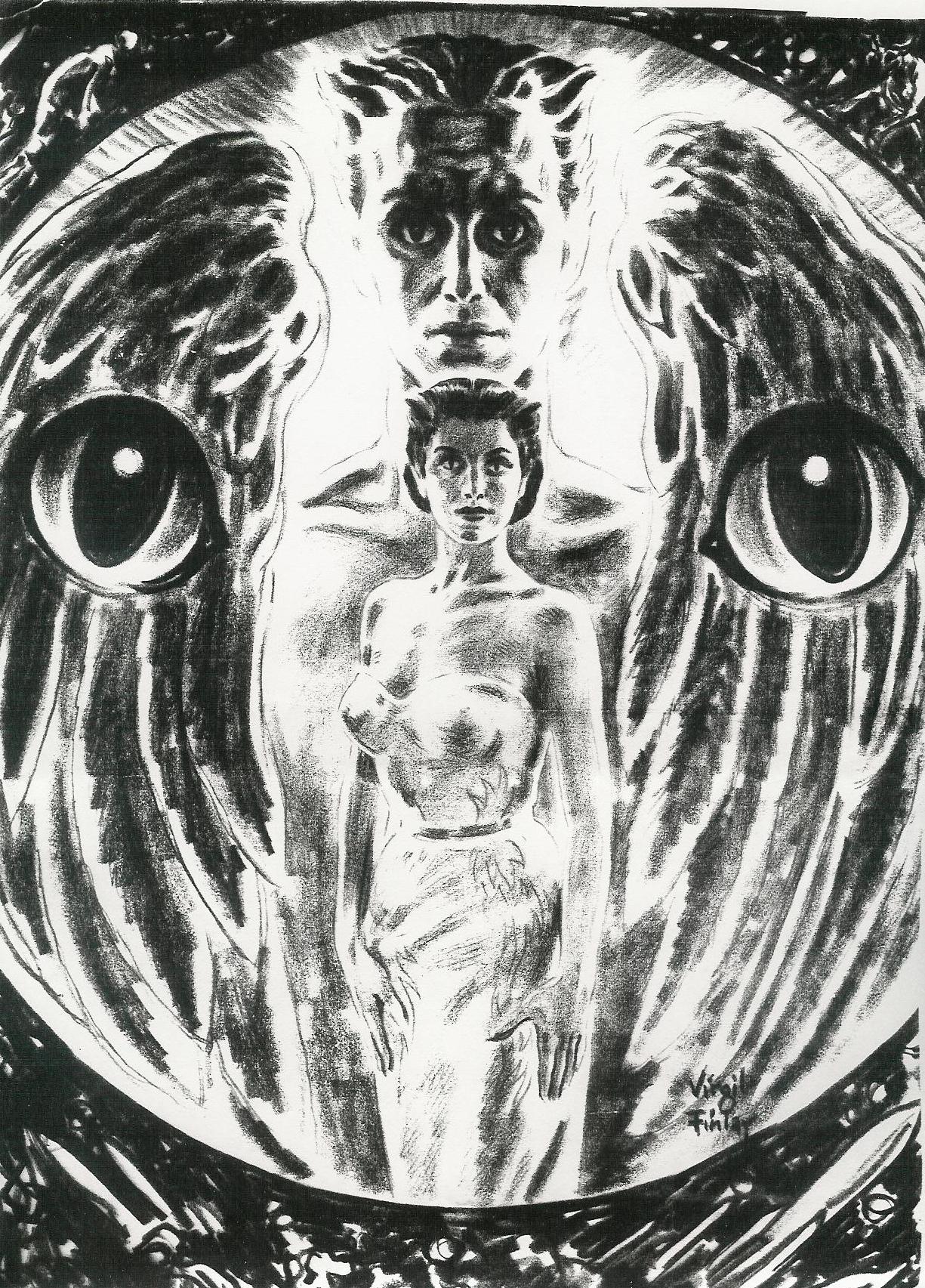

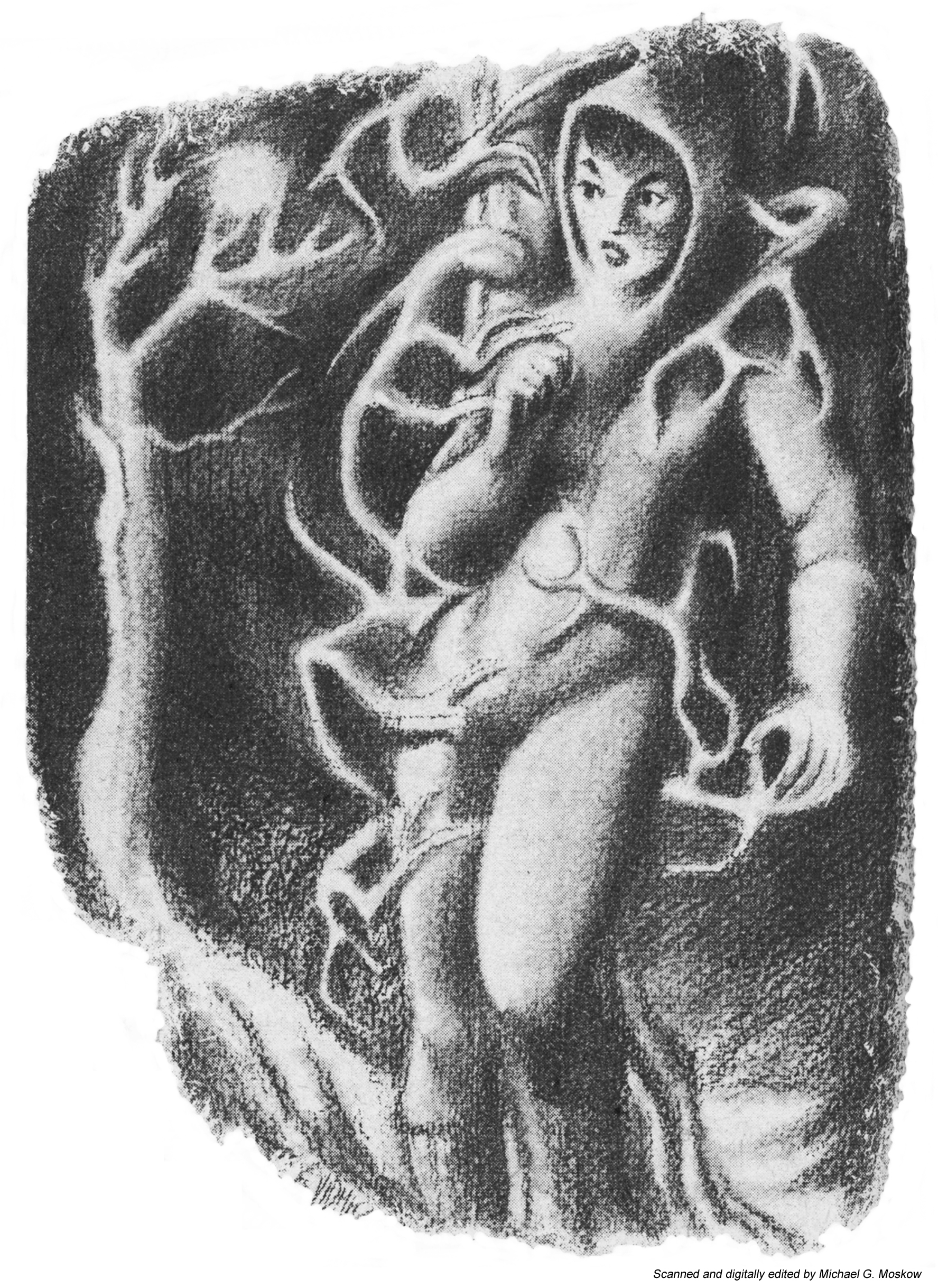

Symbolic illustration of Scully La Cruz (facing title page) by Jack Gaughan.

________________________________________

________________________________________

From rear cover …

“Scully La Cruz was a Thin – a muscleless free-fall phenomenon whose home was the Sack circling the Moon, who could only support life in Earth-gravity conditions by having himself encased in a titanium exo-sekleton. To the inhabitants of the ravaged post-war Earth, he looked spectrally outlandish.

To Scully, the inhabitants of the Earth looked equally odd. Because the U.S.A. had disappeared in the aftermath of the atomic conflict and had been replaced by Greater Texas. And Greater Texas was dominated by the Greater Texans, masterful giants created by hormone treatments, who strode lordly about amidst their dwarvish peons and slaves.

To these unhappy underlings, Scull appeared as a Sign, a leader for revolt. To Scully, this reverence sparked his actor instinct sufficiently to make him decide to accept that role.

This is one of Fritz Leiber’s most astonishing and satirical novels … a caricature of the future as living, chilling and ultimately serious of purpose as a Jules Feiffer cartoon.”

Excerpt (from pages 14-15) …

They were looking I discovered, at a handsome,

shapely,

dramatic-featured man,

eight feet eight inches tall and massing 147 pounds

and ninety-seven pounds without his exoskeleton.

Except for relaxed tiny bulges of muscle in his forearms and calves

(latter to work lengthy toes, useful in gripping),

this man was composed of skin, bones, ligaments, fasciae, narrow arteries and veins,

nerves, small-size assorted inner organs, ghost muscles,

and a big-domed skull with two bumps of jaw muscles.

He was wearing a skintight black suit that left bare only his sunken-chested,

deep-eyed, beautiful tragic face and big, heavy-tendoned hands.

This truly magnificent,

romantically handsome,

rather lean man was standing on two corrugated-soled titanium footplates.

From the outer edge of each rose a narrow titanium T-beam that followed the line of his leg,

with a joint (locked now) at the knee,

up to another joint with a titanium pelvic girdle and shallow belly support.

From the back of this girdle a T-spine rose to support a shoulder yoke and rib cage,

all of the same metal.

The rib cage was artistically slotted to save weight,

so that curving strips followed the line of each of his very prominent ribs.

A continuation of his T-spine up the back of his neck in turn supported a snug,

gleaming head basket that rose behind to curve over his shaven cranium,

but it front was little more than a jaw shelf and two inward-curving cheekplates

stopping just short of his somewhat rudimentary nose.

(The nose is not needed in Circumluna to warm or cool air.)

Slightly lighter T-beams than those for his legs reinforced his arms

and housed in their terminal inches his telescoping canes.

Numerous black, foam-padded bands attached this whole framework to him.

A most beautiful prosthetic, one had to admit. While to expect a Thin, or even more than a Fat,

from a free-fall environment to function without a prosthetic on a gravity planet

or in a centrifuge would be the ultimate in cornball ignorance.

Eight small electric motors at the principal joints worked the prosthetic framework

by means of steel cables riding in the angles of the T-beams,

much like antique dentist’s drills were worked, I’ve read.

The motors were controlled by myoelectric impulses from his ghost muscles

transmitted by sensitive pickups buried in the foam-padded bands.

They were powered by an assortment of isotopic and lithium-gold batteries

nesting in his pelvic and pectoral girdles.

“Did this fine man look in the least like a walking skeleton?”

I demanded of myself outragedly.

“Well, yes very much so,”

I had to admit now that I had considered the matter from the viewpoint of strangers.

A very handsome and stylish skeleton,

all silver and black but a skeleton nonetheless,

and one eight feet eight inches tall,

able to look down a little even at the giant Texans around him.

________________________________________

________________________________________

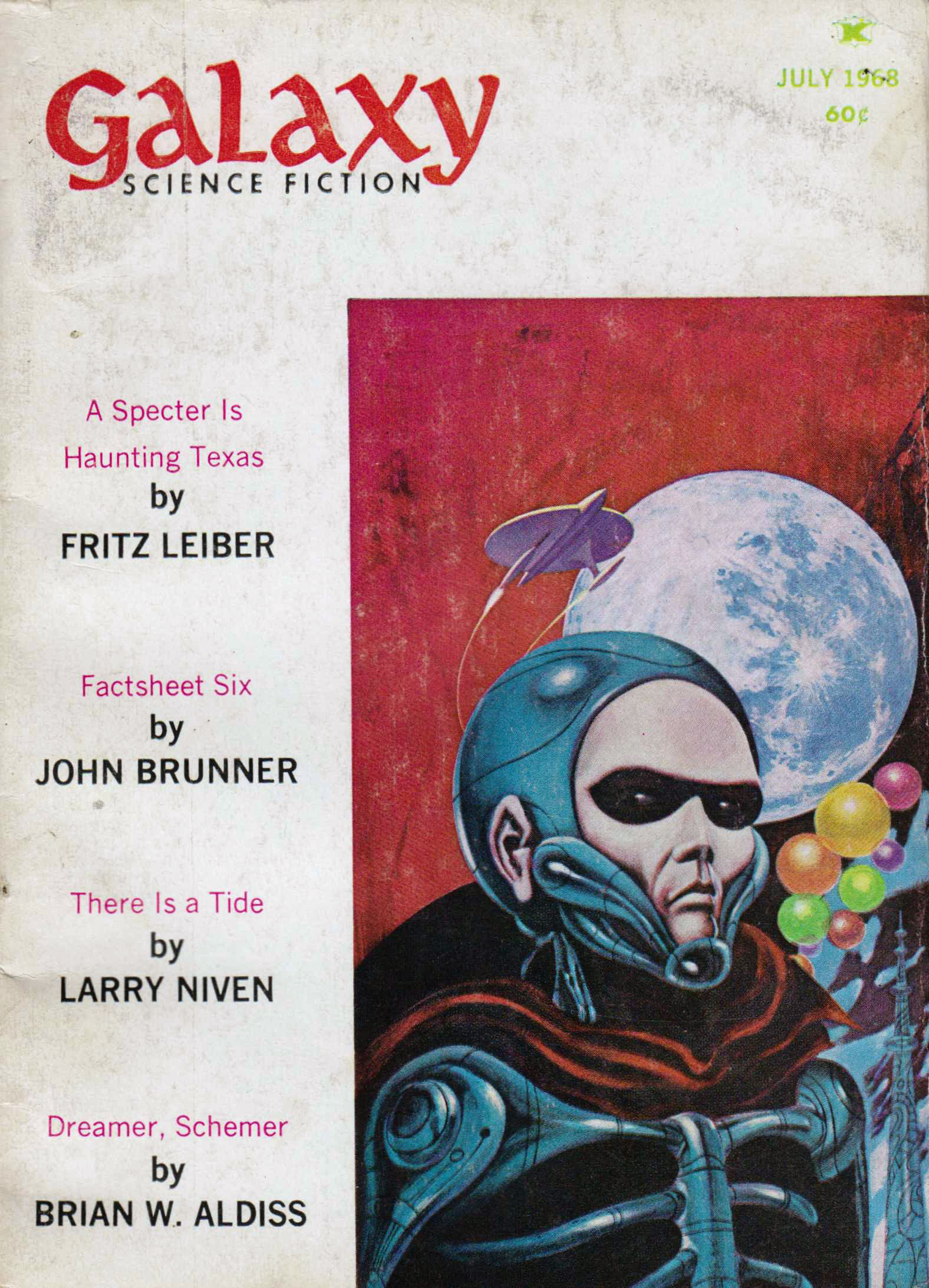

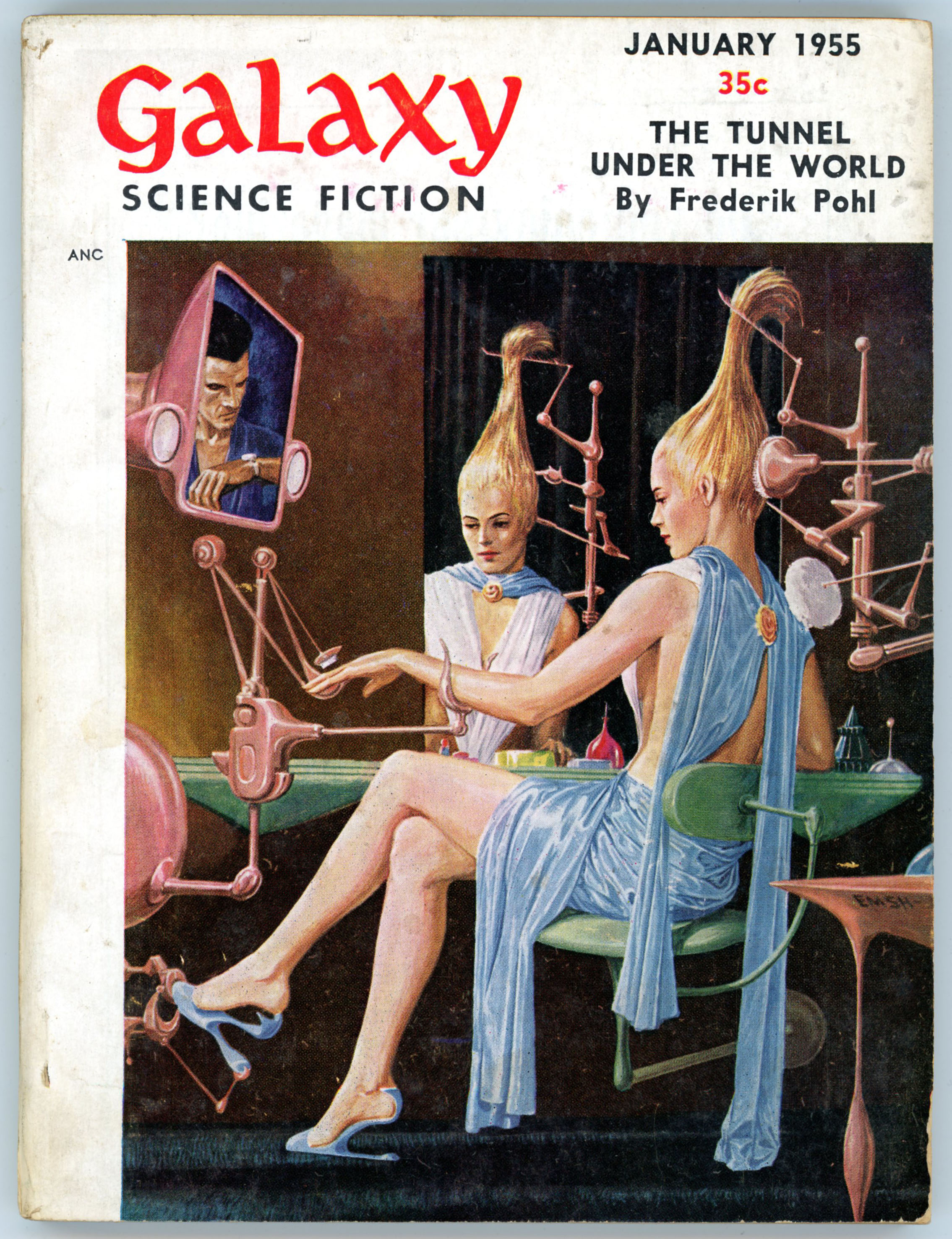

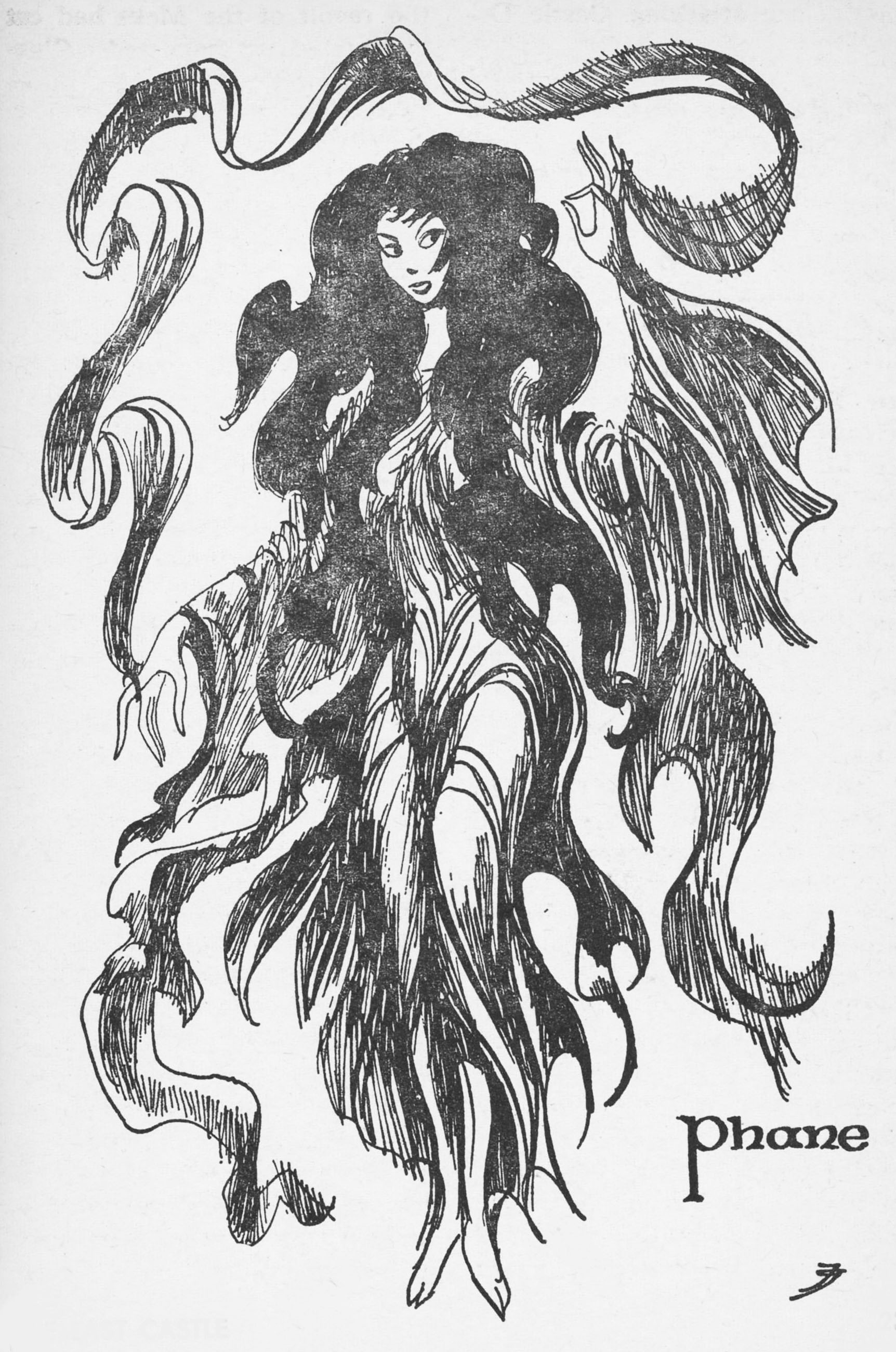

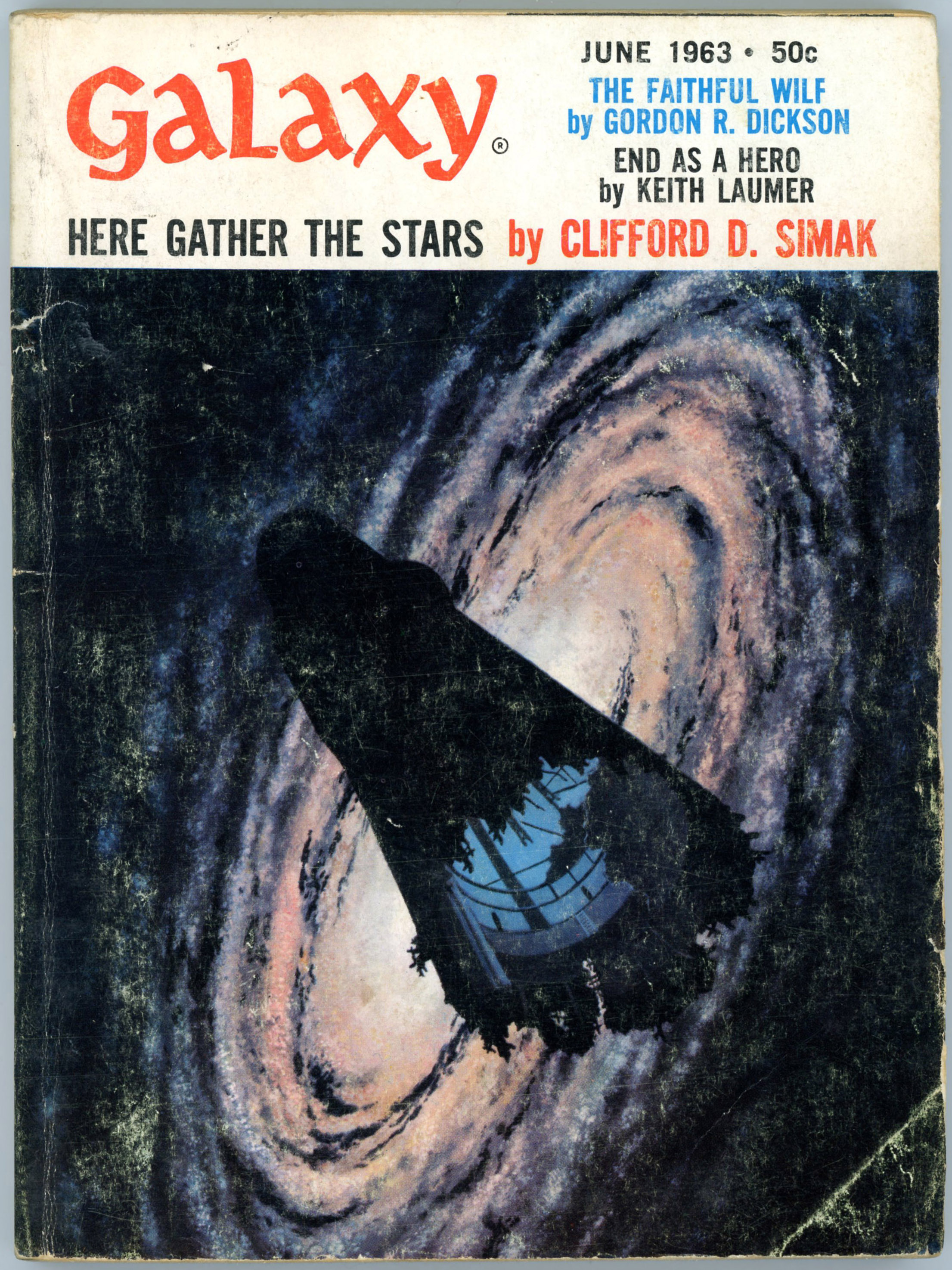

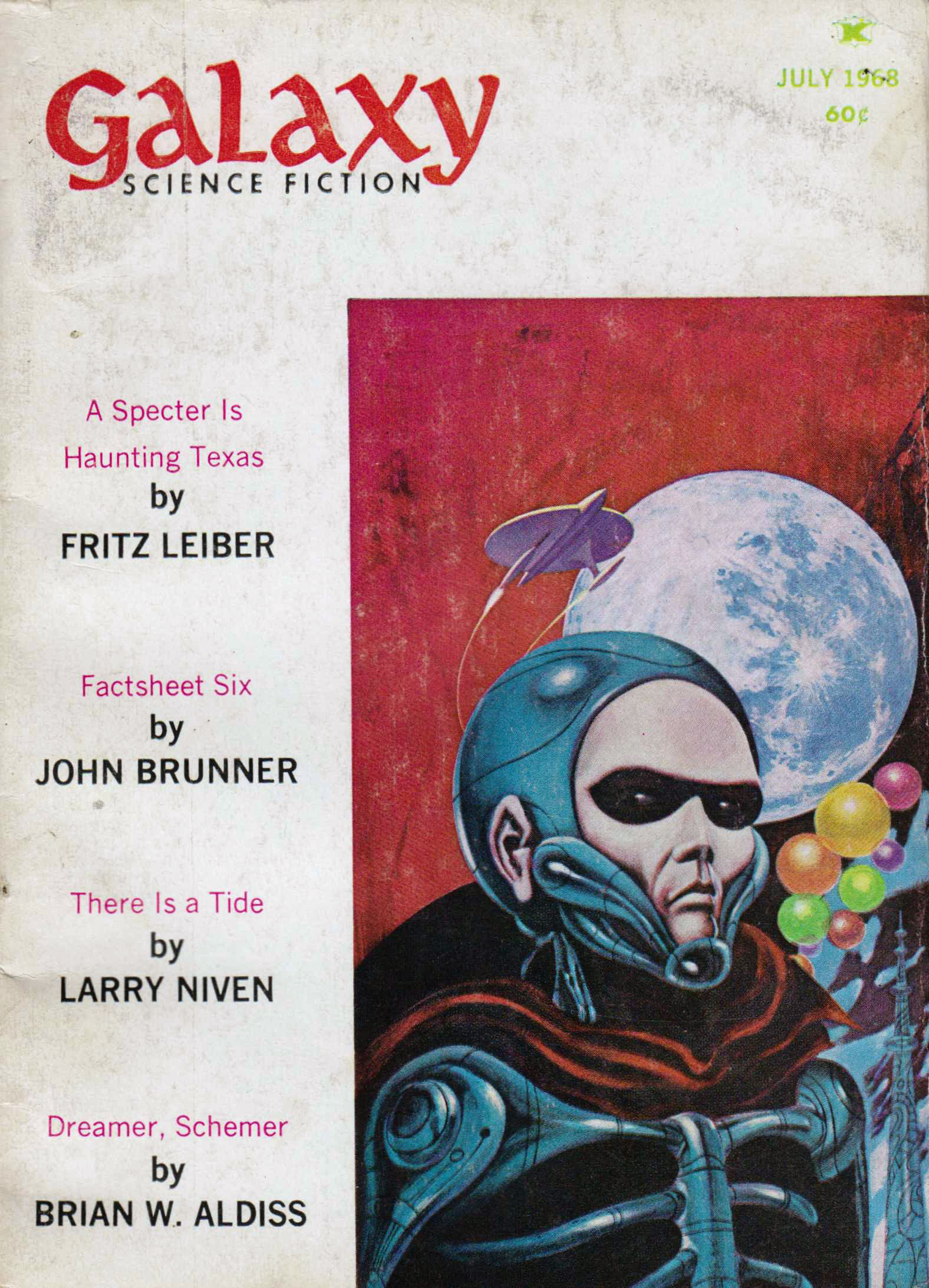

Scully La Cruz, as originally envisioned by Jack Gaughan in Galaxy Science Fiction …

________________________________________

________________________________________

(pp. 6-7)

(pp. 6-7)

________________________________________

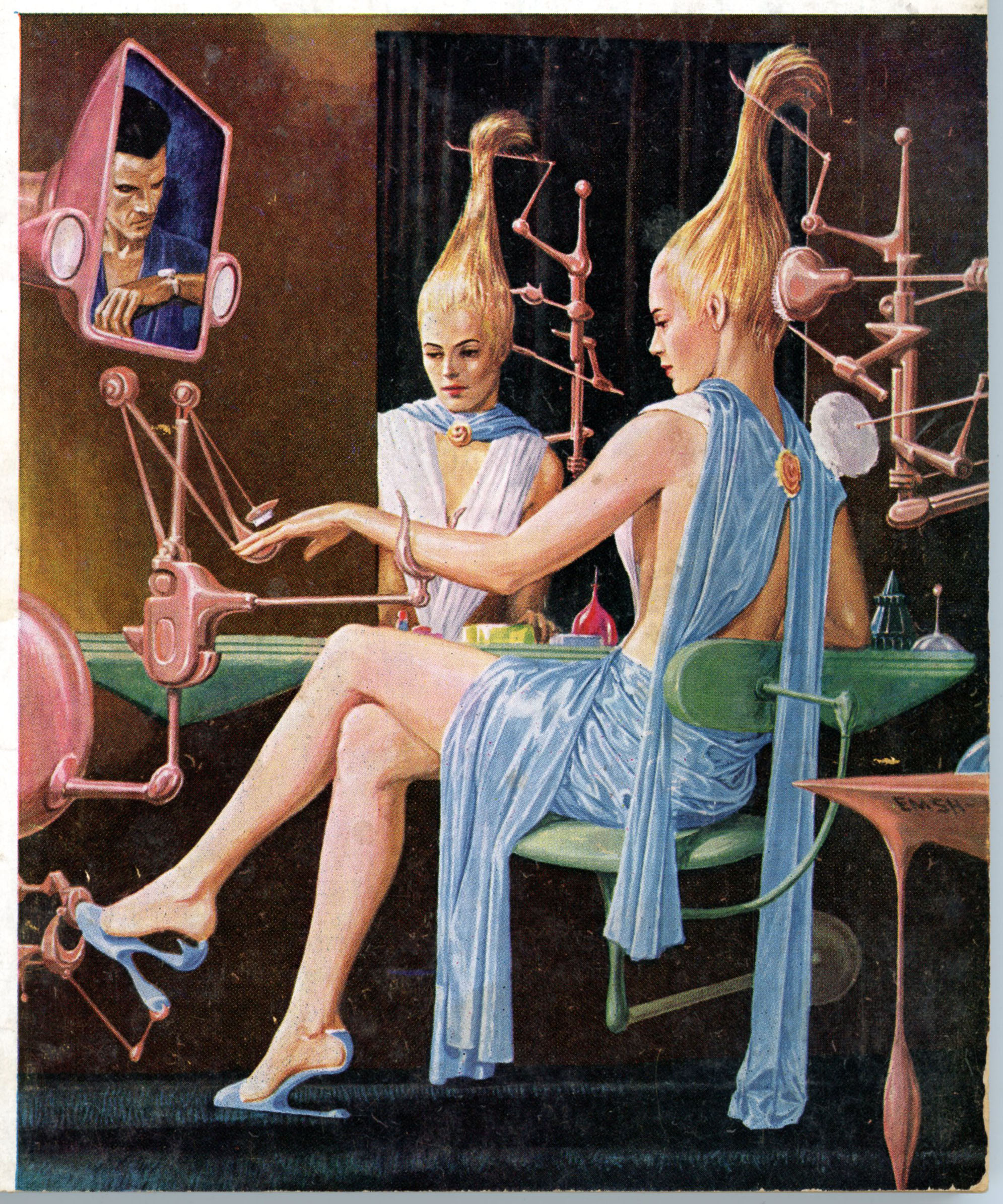

(pp. 28-29)

(pp. 28-29)