Doubleday’s 1958 A Mile Beyond The Moon was the last of three collections of Cyril M. Kornbluth stories to have been published before his death on May 21, 1958. The anthology comprises fifteen stories, of which all but two (“Kazam Collects” and “The Word of Guru”) date from the 1950s.

Though all the stories are emblematic of Kornbluth’s tight, direct, focused writing style, the most memorable are “The Little Black Bag”, “The Words of Guru”, and “Shark Ship”.

Of all the stories within the volume, my favorite is easily “The Little Black Bag”, which – accompanied by Edd Cartier’s great illustrations – first appeared in the July, 1950, issue of Astounding Science Fiction, albeit I first read the story in Volume I of the Science Fiction Hall Of Fame. The story succeeds due to Kornbluth’s clear and uncomplicated plot, adept use of science fiction tropes (time travel and advanced technology), steady and skilled pacing, and crisp – albeit not too deep – character development and individuation, which in combination lead to a conclusion with a jarring and fitting “punch”. Over all, the story reflects the inexorable nature and reach of justice – cosmic justice – regardless of the fact that theology plays no direct role in the tale. This parallels some of Kornbluth’s other works, such as the superb Two Dooms (his much under-appreciated variation on the theme of The Man In The High Castle), and the much shorter Friend To Man.

Fittingly, the story has been adapted for television.

Triply fittingly, it’s been adapted thrice.

Written for broadcast by Kornbluth and Mann Rubin, starring Joseph Anthony as Doctor Arthur Fulbright and Vicki Cummings as “Angie”, it was broadcast on Tales of Tomorrow on May 30, 1952. You can view the program here, at Bobby Jamieson’s YouTube Channel.

Next adapted for the BBC’s science-fiction series Out Of The Unknown (1965-1971), it was broadcast in February of 1969. Though you can read a review of the episode at Archive Television Musings, I don’t believe that it’s available on the Internet. However, perusing the few available stills of the episode suggests that it’s likely the most version most faithful to Kornbluth’s original story.

Later, Rod Serling adapted the story for Night Gallery. Starring the superbly talented Burgess Meredith as Doctor Fulbright, the story was the second of three segments comprising the season’s second episode, broadcast on December 23, 1970.

You can view Night Gallery version (with Spanish subtitles) in three segments (first, second, and third) via Metatube.

Though I’ve not fully viewed the Tales and Tomorrow and Night Gallery versions of the story, it seems clear that – along with character changes – the story in those two productions was substantially softened from the disconcerting (shall we say…?!) “events” in the original tale in Astounding.

Well, he never flinched with words.

And so, the book’s cover…

(Hardback – “Hard Landing!”)

Abraham R. Charlip’s cover fits the title perfectly: A symbolic moonscape with a strangely greenish hue, filled with meteor craters, is viewed from directly above – from a mile above? – albeit the height of the crater walls is greatly exaggerated! Unusually for science fiction art of this era, neither astronauts nor spacecraft nor aliens are part of the picture.

Abraham R. Charlip’s cover fits the title perfectly: A symbolic moonscape with a strangely greenish hue, filled with meteor craters, is viewed from directly above – from a mile above? – albeit the height of the crater walls is greatly exaggerated! Unusually for science fiction art of this era, neither astronauts nor spacecraft nor aliens are part of the picture.

Here’s the blurb from the anthology’s rear cover, which – along with the rocket, and emblem in the lower right corner – was a regular feature on the covers of hardbound science fiction published by Doubleday during the 1950s. (You can view a similar example on the cover of A.E. Van Vogt’s Triad.) Thus, the blurb:

TODAY’S FICTION –

TOMORROW’S FACTS

LIFE Magazine says there are more than TWO MILLION science fiction fans in this country. From all corners of the nation comes the resounding proof that science fiction has established itself as an exciting and imaginative NEW FORM OF LITERATURE that is attracting literally tens of thousands of new readers every year!

Why? Because no other form of fiction can provide you with such thrilling and unprecedented adventures! No other form of fiction can take you on an eerie trip to Mars … amaze you with a journey into the year 3000 A.D. … or sweep you into the fabulous realms of unexplored Space! Yes, it’s no wonder that this exciting new form of imaginative literature has captivated the largest group of fascinated new readers in the United States today!

Note the lack of reference to the book’s content, let alone other works of science fiction published by Doubleday. Instead, the cover blurb does something very different: It validates the cultural and literary legitimacy of science fiction as a form of literature, and indirectly (hint-hint, wink-wink, nod-nod!) praises – albeit tangentially – those readers who have an interest in the genre. Though you’d never see such verbiage today – some sixty years later – in the 1950s this would actually have made sense, in terms of culturally validating a form of literature long steeped in negative stereotypes.

And so, the anthology’s includes are listed below. I’ve included illustrations for the June, 1941 issue of Stirring Science Stories, and the May, 1953, issue of Space Science Fiction, which has a stunning and imaginative cover by Alex Ebel, and interior art by Frank Kelly Freas.

Contents

Make Mine Mars, from Science Fiction Adventures, November, 1952

The Meddlers, from Science Fiction Adventures, September, 1953

The Events Leading Down to the Tragedy, from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, January, 1958

The Little Black Bag, from Astounding Science Fiction, July, 1950

Everybody Knows Joe, from Fantastic Universe, October-November, 1953

Time Bum, from Fantastic, January-February, 1953

Passion Pills, from A Mile Beyond the Moon (this volume)

Virginia, from Venture Science Fiction, March, 1958

The Slave, from Science Fiction Adventures, September, 1957

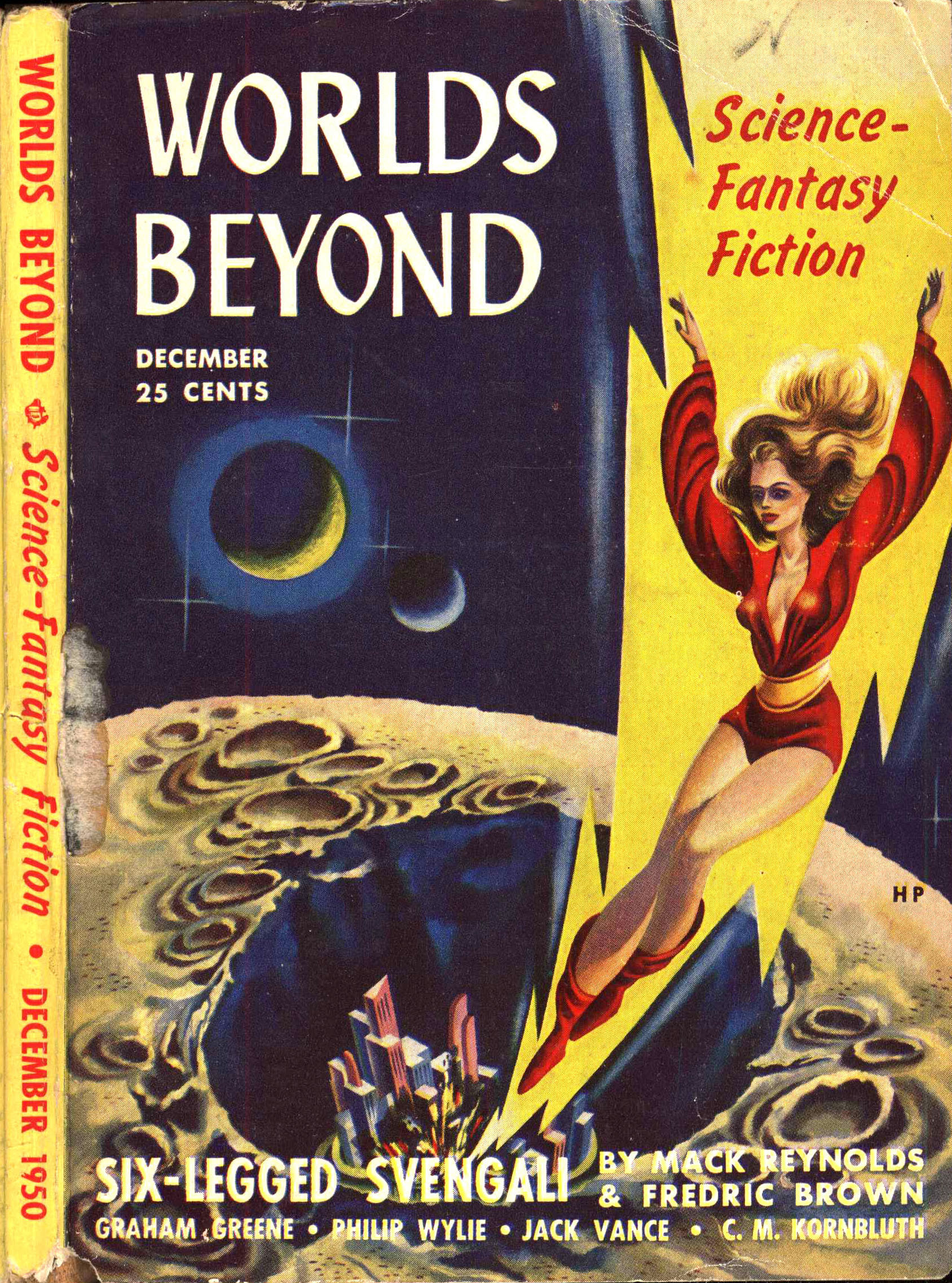

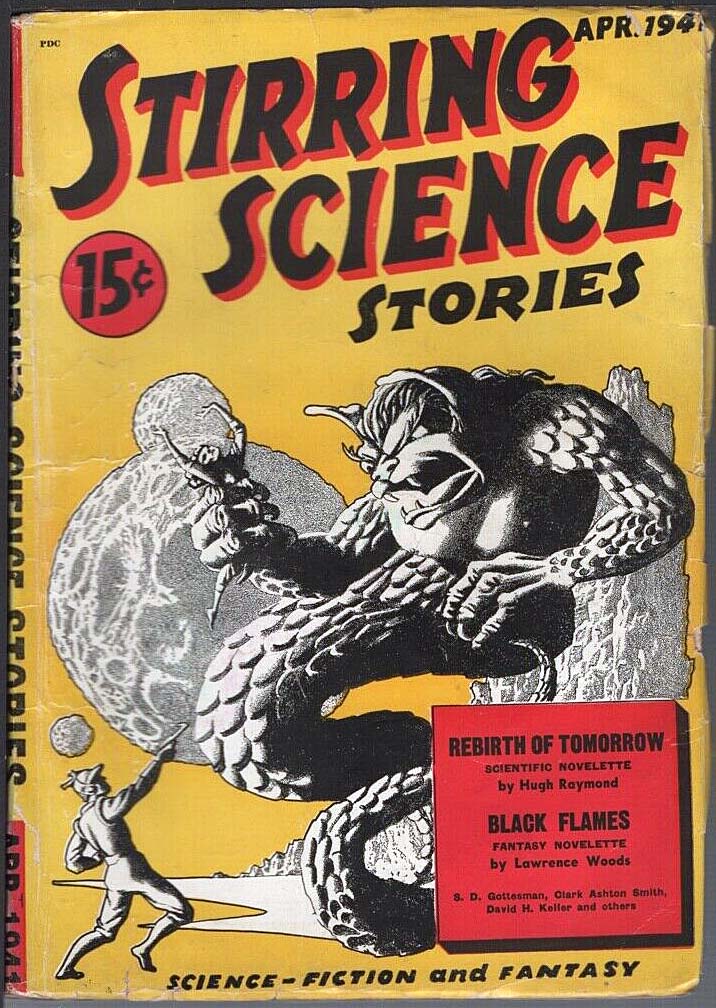

Kazam Collects, from Stirring Science Stories, June, 1941 (as S.D. Gottesman) (Cover by Hannes Bok)

The Last Man Left in the Bar, from Infinity Science Fiction, October, 1957

The Last Man Left in the Bar, from Infinity Science Fiction, October, 1957

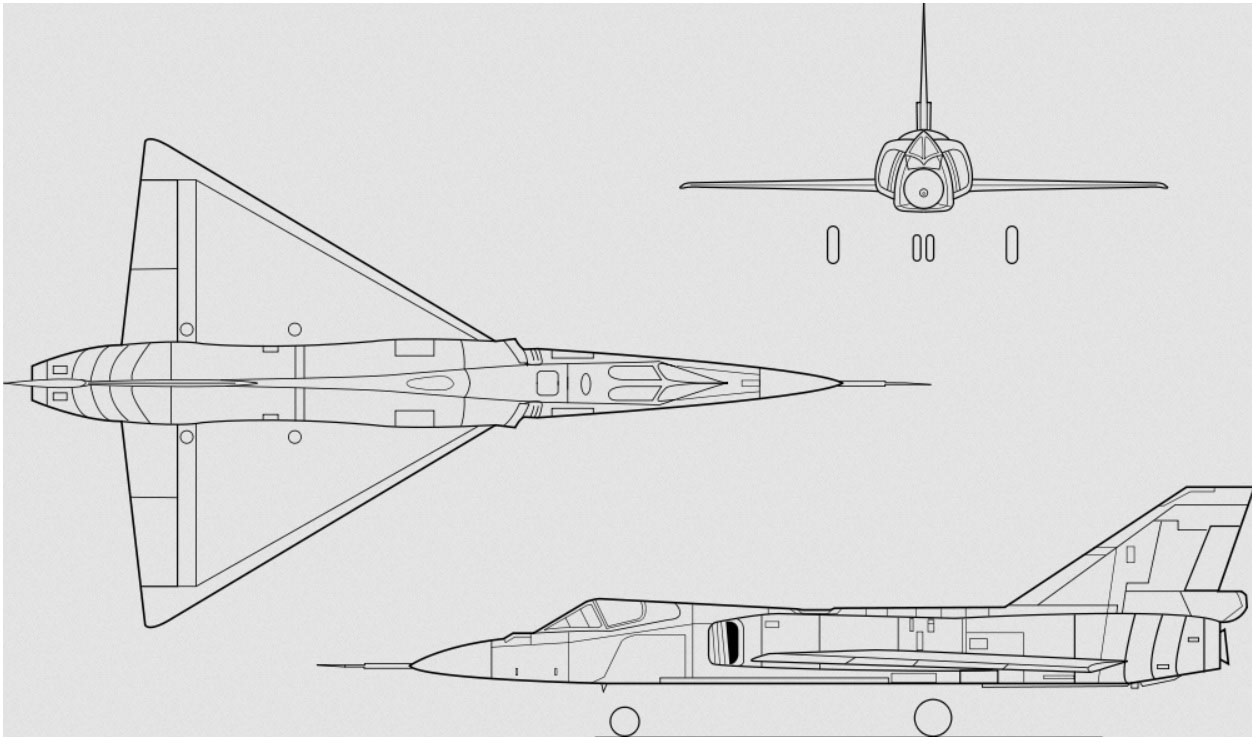

The Adventurer, from Space Science Fiction, May, 1953 (Cover by Alex Ebel)

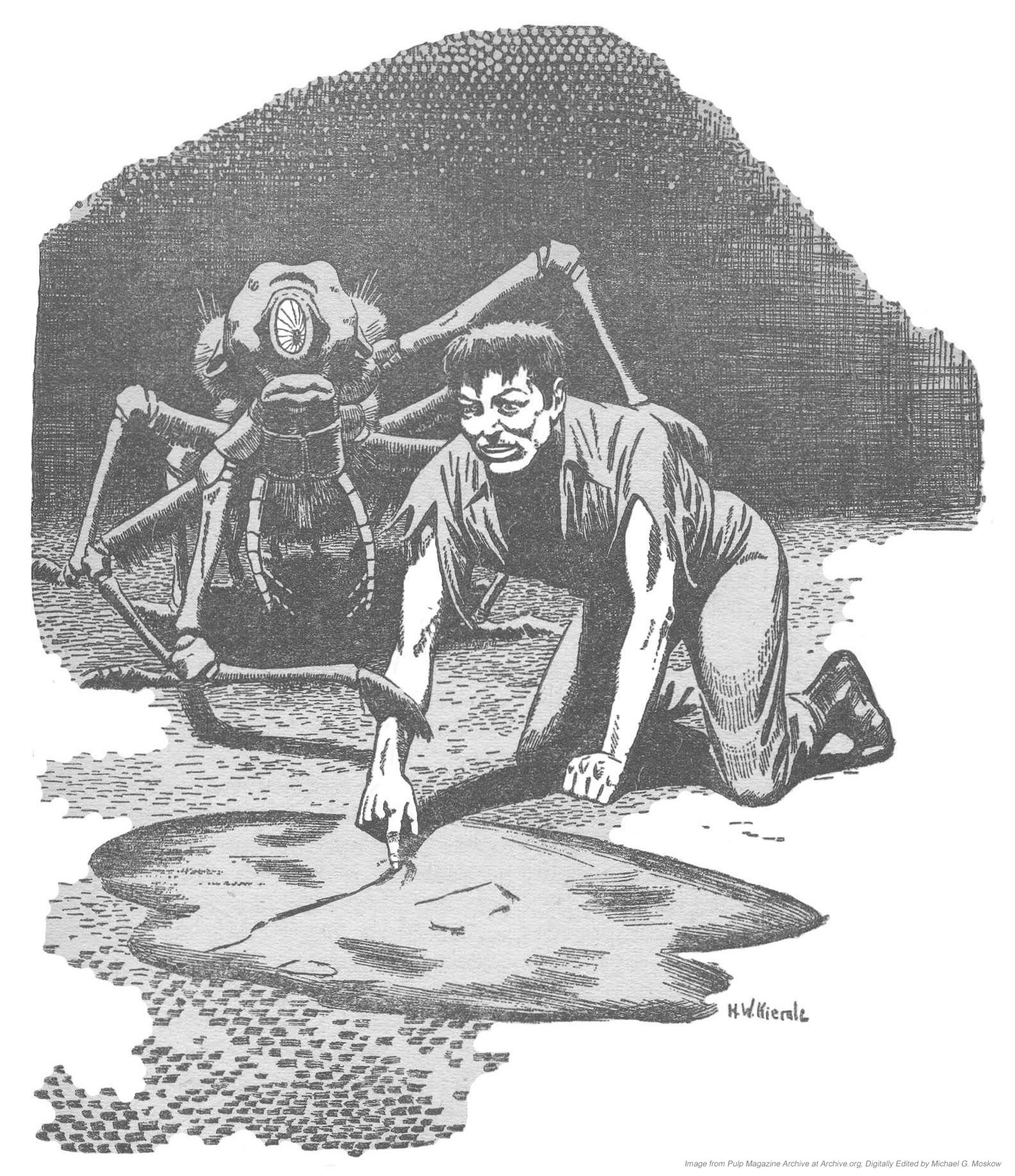

Interior illustration (p. 45) by Frank Kelly Freas

Interior illustration (p. 45) by Frank Kelly Freas

The Words of Guru, from Stirring Science Stories, June, 1941 (as Kenneth Falconer)

The Words of Guru, from Stirring Science Stories, June, 1941 (as Kenneth Falconer)

Shark Ship, from A Mile Beyond the Moon (this volume; variant of “Reap the Dark Tide”, from Vanguard Science Fiction, June, 1958 (First issue, last issue, only issue! – alas!)

Two Dooms, from Venture Science Fiction, July, 1958

______________________________

Also in Stirring Science Stories, June, 1941 but not included in this anthology:

Forgotten Tongue (as Walter C. Davies)

Mr. Packer Goes to Hell (as Cecil Corwin), related to “Thirteen O’Clock”, in Stirring Science Stories, February, 1941

______________________________

(Paperback – “Soft Landing!”)

The anthology was republished in 1962 by Macfadden Books, the paperback imprint of the Macfadden-Bartell Corporation, itself a subsidiary of the Bartell Media Corporation.

Cover painting? Though not specifically listed, the ISFDB indicates that the work was by Richard Powers. If so (okay, it has some elements of Powers’ style!) – alas – this was one of Powers’ weaker (dare I say weakest?) efforts within his otherwise magnificent oeuvre. Well, neither sculptor nor painter nor writer can bat three hundred every time!

Here’s the anthology’s cover blurb, which unlike the Doubleday edition is both entirely relevant to the book’s contents and at the same time perceptive of Kornbluth’s work. One senses that Macfadden’s compiler or editor actually read Kornbluth’s work, to begin with!

DEFT AND FUNNY, WICKED AND WISE…

Here is science fiction at its peak.

C.M. Kornbluth was one of the great masters of the form: gathered here are his best short stories.

This posthumous collection takes you on wild excursions past unexplored boundaries of time and space, society, morals, customs and science. Here are the dilemmas – comic or tragic, ironic or fantastic – that confront the individual when technology advances relentlessly past humanity’s capacity to absorb it.

These stories are never horse-operas with Martian settings. They are sensitive, superbly written, humanity-conscious tales of people struggling in a world they might have made – but never mastered.

I wonder how Kornbluth would have treated smartphones (oxymoron…), Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and all the chaotic melange that comprises “social media”…

______________________________

______________________________

For your further enjoyment, enlightenment, and distraction…

Internet Speculative Fiction Database, for A Mile Beyond the Moon

Abraham Remy Charlip, at Wikipedia

Cyril M. Kornbluth, at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Night Gallery – The Little Black Bag, with Spanish Subtitles (part 1), at Metatube

Night Gallery – The Little Black Bag, with Spanish Subtitles (part 2), at Metatube

Night Gallery – The Little Black Bag, with Spanish Subtitles (part 3), at Metatube

Night Gallery, at Wikipedia

Night Gallery – List of Episodes, at Wikipedia

Tales of Tomorrow, at Internet Movie Database

Tales of Tomorrow – Little Black Bag, at Bobby Jamieson’s YouTube Channel